The Cabinetry Heritage of Japan

When one thinks of traditional Japan, many images come to mind: cherry blossoms, folding screens of gold, formidable swords, rustic tea bowls. These items reflect a profound depth of aesthetic concern and are infused with cultural meaning. There is a less well known subject of Japan’s aesthetic and craft heritage: its cabinetry.

Japanese antique cabinetry is known as tansu. Tansu is a collective term denoting a vast array of cabinet designs for a myriad of uses. These include ship’s strong boxes, families clothing storage, peddler’s chest and kitchen cupboards. Some tansu also functioned as a staircase. Tansu reflect what Japanese treasured and safeguarded, used daily and kept private.Tansu held swords, valuables, tea utensils, fine kimono, documents, foodstuffs and tools.

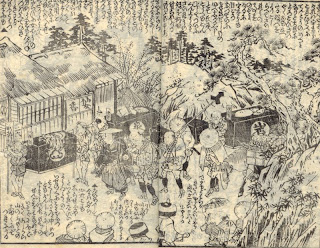

These events occurred in an environment of peace, which was ushered in by the victories of Tokugawa forces after the Battle of Sekigahara and then with the fall of Osaka castle in 1615. Thereafter the Tokugawa family ruled the newly unified Japan for over 250 years. This time is referred to as the Edo period, named after the new capital of Edo. It was a martial society divided into four distinct classes: warrior, farmer, artisan, and merchant.

Stability and predictability were outcomes of a country finally at peace, albeit ruled under strict martial law. Castle towns, port towns and cities grew. Guilds of craftsmen and merchants became more specialized, developing from lumber broker to cabinetmaker. As urban populations grew so did the demand for new and diverse products and for the storage and safekeeping of these items.

Tansu are a good example of this specialization because Tansu are the result of the efforts of three very specialized craftsmen in their production: the cabinetmaker, hardware blacksmith and lacquer finisher.

By 1600 a new saw was commonly seen called the mae biki oga or one man rip saw. Kyoto/Kansai area blacksmiths developed this saw during the final years of the Momoyama period. It effectively allowed one man to do the work of two and doubled the production of thin boards, so necessary to the production of tansu. In addition to the rip saw the smoothing plane evolved from a pushed Chinese model into a pulled version by 1615.

Finally, cotton played its own role in the history of tansu as can be seen because the majority of tansu were for clothing storage. Cotton was first used in samurai attire but quickly spread to garments for the lower classes as its cultivation spread and affordability with it. It was easier to dye and wash and was more comfortable than hemp and paper garments.

Although the military ruled the Edo period, it was in many ways, the era of the merchant and craftsman. It was the merchant and artisan that prospered from the peace allowing them to develop the real power, economic power. By the end of the Edo period the martial society represented by the samurai was indebted and fragmented and unsettled by encroachments from the west. The restoration of the Emperor Meiji ushered in an age (1868-1912) of civilian authority and class distinctions fell to economic freedoms. Tansu developed from previous cottage industries into vital regional designs produced for ever larger markets. We know many of these designs by the towns associated with them: Sendai, Ogi, Yonezawa, Sakata, Nagoya, and Mikuni to name but a few.

By the end of the Meiji period new industrial techniques and machinery had made inroads into tansu design and compulsory public education began to thwart a tradition of learning from craftsman to apprentice. A headlong rush to imitate the industrial successes of the west would seal tansu’s fate. Taisho (1912-1926) period tansu reflected popular consumption of western dress and aesthetics. Tansu design was ever more subject to economics and industrial technique. While tansu were made into the Showa era (1926-1989) the fascinating regional designs with hand-forged iron that represented tansu’s heyday faded

Tansu is historical cabinetry created with a distinctive use of wood and iron fittings, sometimes lacquered, sometimes not. They embody Japanese aesthetic ideals such as asymmetry, rusticity, and quiet elegance, even perishability. And yet tansu have lasted the ages and have crossed an ocean. They have now influenced a generation of western craftsmen.

Tansu represent a distinct albeit overlooked chapter in Japanese craft history, indeed they were the repositories of that history as well as being players in it. Storage has never received the recognition or documentation architecture has, we hope this exhibition will open some eyes to the recognition that tansu is an integral part of Japan’s craft legacy.

David Jackson

Dane Owen